📢 Publicité

Cours à Domicile

Mathématiques & Physique

Pour lycée et collège

🚀 Parcours d'Excellence

Corrigé Examen National Maths Sciences Maths A et B 2025 Rattrapage

EXERCICE 1 :

Partie I

1)

-

a) Étudier la continuité de \(f\) à droite en 0Corrigé :On utilise la limite usuelle : \[ \lim_{x\to 0^+} x^2 \ln x = 0 \]Par conséquent : \[ \lim_{x\to 0^+} f(x) = \lim_{x\to 0^+} \frac{x^2 \ln x}{x^2 + 1} = \frac{0}{1} = 0 = f(0) \]\(\text{Donc } f \text{ est continue à droite en 0.}\)

-

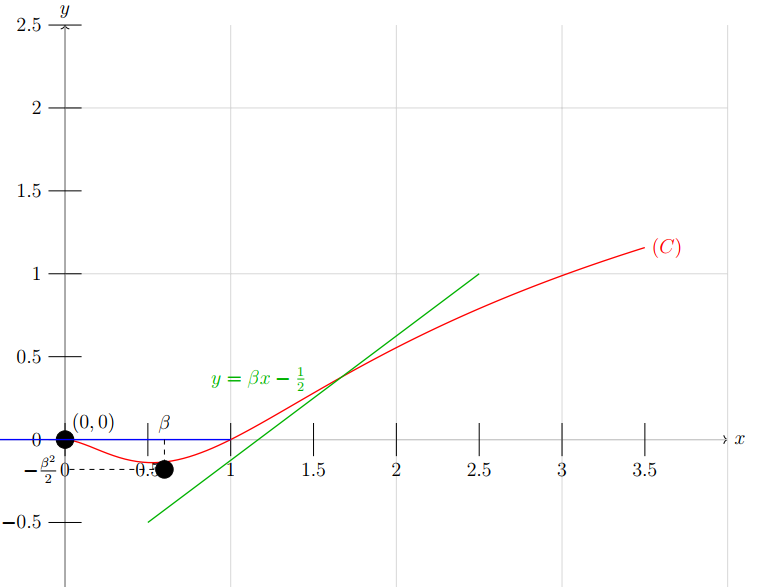

b) Étudier la dérivabilité de \(f\) à droite en 0 puis interpréter graphiquement\[ \lim_{x\to 0^+} \frac{f(x) - f(0)}{x - 0} = \lim_{x\to 0^+} \frac{x^2 \ln x}{x(x^2 + 1)} = \lim_{x\to 0^+} \frac{x \ln x}{x^2 + 1} \]On utilise la limite usuelle : \[ \lim_{x\to 0^+} x \ln x = 0 \] Donc : \[ \lim_{x\to 0^+} \frac{f(x) - f(0)}{x - 0} = \frac{0}{1} = 0 \]\(f \text{ est dérivable à droite en 0 et } f'_d(0)=0\)Interprétation graphique : La courbe \((C)\) admet une demi-tangente horizontale à droite au point \((0,0)\).

-

c) Calculer \(\lim_{x\to +\infty} f(x)\) et \(\lim_{x\to +\infty}\dfrac{f(x)}{x}\) puis interpréterCorrigé :\[ \lim_{x\to +\infty} f(x)=\lim_{x\to +\infty} \frac{x^2 \ln x}{x^2 + 1} = \lim_{x\to +\infty} \frac{\ln x}{1 + 1/x^2} = +\infty \] \[ \lim_{x\to +\infty} \frac{f(x)}{x} = \lim_{x\to +\infty} \frac{x \ln x}{x^2 + 1} = \lim_{x\to +\infty} \frac{\frac{\ln x}{x}}{1+\frac{1}{x^2}} = 0 \]\(\text{La courbe }(C)\text{ admet une branche parabolique de direction }(Ox)\text{ en }+\infty\)

2)

-

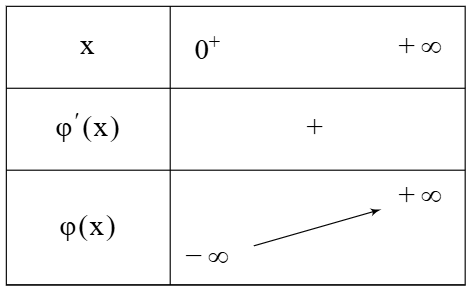

a) Dresser le tableau de variations de \(\varphi\)Corrigé :\(\varphi(x) = x^2 + 1 + 2\ln x\)Dérivée : \[ \varphi'(x)=2x+\frac{2}{x}>0 \quad \forall x>0 \]

-

b) Montrer que \(\varphi(x)=0\) admet une solution unique \(\beta\in\left]\frac12;\frac{1}{\sqrt3}\right[\)Corrigé :

- Sur l’intervalle \(\left[\frac12,\frac1{\sqrt3}\right]\subset]0,+\infty[\), la fonction \(\ln(x)\) est continue, donc \(\varphi(x)=x^2+1+2\ln(x)\), somme de fonctions continues, est continue sur \(\left[\frac12,\frac1{\sqrt3}\right]\).

- Calculons les valeurs aux bornes : \[ \varphi\!\left(\tfrac12\right) =\tfrac14+1+2\ln\!\left(\tfrac12\right) \approx 1.25-1.4=-0.15<0 \] \[ \varphi\!\left(\tfrac1{\sqrt3}\right) =\tfrac13+1+2\ln\!\left(\tfrac1{\sqrt3}\right) \approx 1.33-1.1=0.23>0 \]

- Ainsi, \(\varphi\!\left(\frac12\right)\, \varphi\!\left(\frac1{\sqrt3}\right)<0\)

- De plus \(\varphi\) est strictement croissante sur \(]0,+\infty[\), en particulier sur \(\left[\frac12,\frac1{\sqrt3}\right]\).

\(\exists!\,\beta\in\left]\frac12,\frac1{\sqrt3}\right[ \text{ tel que } \varphi(\beta)=0\) -

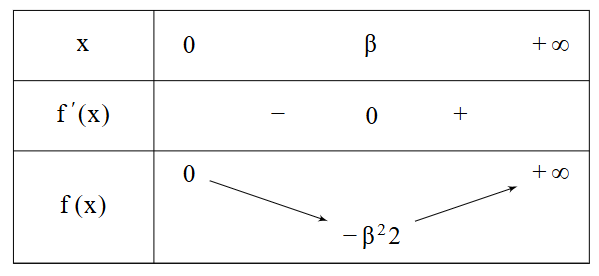

c) Montrer que \(f(\beta)=-\dfrac{\beta^2}{2}\)Corrigé :\[ \varphi(\beta)=0 \Rightarrow \beta^2+1+2\ln\beta=0 \Rightarrow \ln\beta=-\frac{\beta^2+1}{2} \] \[ f(\beta)=\frac{\beta^2\ln\beta}{\beta^2+1} =\frac{\beta^2\left(-\frac{\beta^2+1}{2}\right)}{\beta^2+1} =-\frac{\beta^2}{2} \]\(f(\beta)=-\dfrac{\beta^2}{2}\)

3)

-

a) Montrer que \(f\) est dérivable sur \(]0;+\infty[\) et calculer \(f'(x)\)Corrigé :

La fonction \(x\mapsto x^2\ln x\) est dérivable sur \(]0,+\infty[\) (produit de fonctions dérivables), et la fonction \(x\mapsto x^2+1\) est dérivable sur \(\mathbb{R}\) et ne s’annule pas sur \(]0,+\infty[\).

Donc la fonction \( f(x)=\frac{x^2\ln x}{x^2+1} \) est dérivable sur \(]0,+\infty[\).Pour tout \(x\) de \(]0,+\infty[\): \[ f'(x) =\frac{(x^2\ln x)'(x^2+1)-(x^2\ln x)(x^2+1)'}{(x^2+1)^2} \] \[ =\frac{(2x\ln x+x)(x^2+1)-2x(x^2\ln x)}{(x^2+1)^2} \] \[ =\frac{2x\ln x(x^2+1)+x(x^2+1)-2x^3\ln x}{(x^2+1)^2} \] \[ =\frac{x\big(x^2+1+2\ln x\big)}{(x^2+1)^2} \] \[ =\frac{x\,\varphi(x)}{(x^2+1)^2} \]\(f'(x)=\dfrac{x\varphi(x)}{(x^2+1)^2}\) -

b) Donner le tableau de variations de \(f\)Corrigé :

- \(\varphi\) s’annule en \(\beta\), négative avant, positive après.

- Le dénominateur \((x^2+1)^2>0\).

-

c) Montrer que \(\dfrac1\beta\) est l’unique solution de \(f(x)=\dfrac12\) sur \(]\beta;+\infty[\)Corrigé :Calculons la valeur de \(f\) en \(\dfrac1\beta\) : \[ f\!\left(\frac1\beta\right) =\frac{(1/\beta)^2\ln(1/\beta)}{(1/\beta)^2+1} =\frac{-\ln\beta}{\beta^2+1} \] Or, d’après la question précédente, \[ \ln\beta=-\frac{\beta^2+1}{2}. \] Donc : \[ f\!\left(\frac1\beta\right)=\frac12. \]De plus, \(f\) est strictement croissante sur \(]\beta,+\infty[\). Par conséquent, l’équation \(f(x)=\dfrac12\) admet unique solution sur \(]\beta,+\infty[\).\(\dfrac1\beta\) est l’unique solution de \(f(x)=\dfrac12\) sur \(]\beta,+\infty[\)

-

d) Montrer que \(y=\beta x-\dfrac12\) est la tangente à \((C)\) en \(x=\dfrac1\beta\)Corrigé :

On a :

\[ f\!\left(\frac{1}{\beta}\right)=\frac{1}{2} \]On a :

\[ f'(x)=\frac{x\,\varphi(x)}{(x^2+1)^2} \]Donc :

\[ f'\!\left(\frac{1}{\beta}\right) = \frac{\frac{1}{\beta}\,\varphi\!\left(\frac{1}{\beta}\right)} {\left(\left(\frac{1}{\beta}\right)^2+1\right)^2} \] \[ \varphi\!\left(\frac{1}{\beta}\right) = \left(\frac{1}{\beta}\right)^2+1+2\ln\!\left(\frac{1}{\beta}\right) \] \[ = \frac{1}{\beta^2}+1-2\ln(\beta) \] \[ = \frac{1}{\beta^2}+1+(\beta^2+1) \quad\text{car }\varphi(\beta)=0\Rightarrow \ln(\beta)=-\frac{\beta^2+1}{2} \] \[ = \frac{1}{\beta^2}+\beta^2+2 \] \[ f'\!\left(\frac{1}{\beta}\right) = \frac{\frac{1}{\beta}\left(\frac{1}{\beta^2}+\beta^2+2\right)} {\left(\frac{1+\beta^2}{\beta^2}\right)^2} \] \[ = \frac{\frac{1}{\beta^3}+\beta+\frac{2}{\beta}} {\frac{(1+\beta^2)^2}{\beta^4}} \] \[ = \left(\frac{1+\beta^4+2\beta^2}{\beta^3}\right)\times \frac{\beta^4}{(1+\beta^2)^2} \] \[ = \frac{\beta(1+\beta^4+2\beta^2)}{(1+\beta^2)^2} = \frac{\beta(1+\beta^2)^2}{(1+\beta^2)^2} = \beta \]Équation de la tangente :

\[ y = f'\!\left(\frac{1}{\beta}\right)\left(x-\frac{1}{\beta}\right) + f\!\left(\frac{1}{\beta}\right) \] \[ = \beta\left(x-\frac{1}{\beta}\right)+\frac{1}{2} = \beta x - 1 + \frac{1}{2} = \beta x - \frac{1}{2} \]\(\text{La droite } y=\beta x-\frac12 \text{ est bien la tangente à }(C)\text{ en }x=\frac1\beta\)

4) Représentation graphique

Partie II

1)

-

a) Étudier les variations de \(g\)Corrigé :La fonction est définie par : \( g(x)=\sqrt{e^{\,1+\frac{1}{x^2}}} =e^{\frac12\left(1+\frac{1}{x^2}\right)} \)Donc: \( g'(x) = e^{\frac12\left(1+\frac{1}{x^2}\right)} \times \left(-\frac{1}{x^3}\right) = -\frac{e^{\frac12\left(1+\frac{1}{x^2}\right)}}{x^3} \)Or, pour tout \(x>0\), on a \(e^{\frac12\left(1+\frac{1}{x^2}\right)}>0\) et \(x^3>0\), donc : \[ g'(x)<0 \quad \forall x>0. \]\(g\) est strictement décroissante sur \(]0;+\infty[\)

-

b) Montrer que : \( \forall x \in J,\ \sqrt{3} < g(x) < 2 \)Corrigé :

On considère \(J=[\sqrt{3},\,2]\). Comme \(g\) est décroissante sur \(]0,+\infty[\), on a :

\[ g(2)\le g(x)\le g(\sqrt{3})\quad (x\in J) \] \[ g(\sqrt{3}) = e^{\frac12\left(1+\frac{1}{3}\right)} = e^{\frac23}\approx 1.95 \qquad\text{et}\qquad g(2)=e^{\frac12\left(1+\frac14\right)}=e^{\frac58}\approx 1.87 \]Donc \(1.87 \le g(x)\le 1.95\). Or \(\sqrt{3}\approx 1.73\), d’où :

\( \forall x\in J,\ \sqrt{3}\lt g(x)\lt 2 \)2)

-

a) En utilisant le résultat de la question I.3-c), montrer que \(g(\alpha)=\alpha\)Corrigé :On a : \[ \alpha=\frac{1}{\beta}. \] Dans la question I.3-c), on a montré que : \[ \ln(\beta)=-\frac{\beta^2+1}{2} \quad\Rightarrow\quad \ln(\alpha)=\ln\!\left(\frac{1}{\beta}\right)=\frac{\beta^2+1}{2}. \]D’autre part, on a : \[ g(x)=\sqrt{e^{\,1+\frac{1}{x^2}}} =e^{\frac12\left(1+\frac{1}{x^2}\right)}. \]Donc : \[ g(\alpha)=e^{\frac12\left(1+\frac{1}{\alpha^2}\right)} \quad\text{et}\quad \ln(\alpha)=\frac12\left(1+\frac{1}{\alpha^2}\right). \] Par conséquent : \[ g(\alpha)=e^{\ln(\alpha)}=\alpha. \]\(g(\alpha)=\alpha\)

-

b) Montrer que : \( \forall x\in J,\ |g'(x)|\le \dfrac{2}{3\sqrt{3}} \)Corrigé :\[ g'(x)=-\frac{g(x)}{x^3} \quad\Rightarrow\quad |g'(x)|=\frac{g(x)}{x^3} \]

Sur \(J=[\sqrt{3},2]\), on a \(g(x)<2\) et \(x\ge \sqrt{3}\Rightarrow x^3\ge 3\sqrt{3}\).

\[ |g'(x)|\le \frac{2}{3\sqrt{3}} \]\( \forall x\in J,\ |g'(x)|\le \dfrac{2}{3\sqrt{3}} \) -

c) En déduire que : \( \forall x\in J,\ |g(x)-\alpha|\le \dfrac{2}{3\sqrt{3}}|x-\alpha| \)Corrigé :La fonction \(g\) est continue sur l’intervalle fermé \(J=[\sqrt{3},\,2]\) et dérivable sur l’intervalle ouvert \(]\sqrt{3},\,2[\).

Soient \(x\in J\) et \(\alpha\in J\).

On applique le théorème des accroissements finis sur l’intervalle d’extrémités \(x\) et \(\alpha\).Par le théorème des accroissements finis, il existe \(c\) compris entre \(x\) et \(\alpha\) tel que : \[ g(x)-g(\alpha)=g'(c)\,(x-\alpha). \]En prenant la valeur absolue, on obtient : \[ |g(x)-\alpha| =|g(x)-g(\alpha)| =|g'(c)|\,|x-\alpha|. \] Or, d’après la question précédente, \[ |g'(c)|\le \frac{2}{3\sqrt{3}} \quad (c\in J). \] Donc : \[ |g(x)-\alpha|\le \frac{2}{3\sqrt{3}}|x-\alpha|. \]\( \forall x\in J,\ |g(x)-\alpha|\le \dfrac{2}{3\sqrt{3}}|x-\alpha| \)

3)

On considère la suite \((x_n)\) définie par : \[ x_0=\frac{7}{4}\quad \text{et}\quad x_{n+1}=g(x_n) \]-

a) Montrer que : \( \forall n\in\mathbb{N},\ x_n\in J \)Corrigé :

Initialisation : \(x_0=\dfrac{7}{4}=1.75\in[\sqrt{3},2]=J\).

Hérédité : si \(x_n\in J\), alors \(x_{n+1}=g(x_n)\in J\) car \(g(J)\subset J\).

Donc, par récurrence : \[ \forall n\in\mathbb{N},\ x_n\in J \]\( \forall n\in\mathbb{N},\ x_n\in J \) -

b) Montrer par récurrence que : \( \forall n\in\mathbb{N},\ |x_n-\alpha|\le \left(\dfrac{2}{3\sqrt{3}}\right)^n |x_0-\alpha| \)Corrigé :

Initialisation (n=0) :

\[ |x_0-\alpha|=\left(\frac{2}{3\sqrt{3}}\right)^0|x_0-\alpha| \]Hérédité : supposons l’inégalité vraie au rang \(n\). Alors :

\[ |x_{n+1}-\alpha| =|g(x_n)-g(\alpha)| \le \frac{2}{3\sqrt{3}}|x_n-\alpha| \] d’où : \[ |x_{n+1}-\alpha| \le \left(\frac{2}{3\sqrt{3}}\right)^{n+1}|x_0-\alpha| \]\( \forall n\in\mathbb{N},\ |x_n-\alpha|\le \left(\dfrac{2}{3\sqrt{3}}\right)^n |x_0-\alpha| \) -

c) En déduire que la suite \((x_n)\) converge vers \(\alpha\)Corrigé :

Comme \( \dfrac{2}{3\sqrt{3}}<1 \), on a :

\[ \left(\frac{2}{3\sqrt{3}}\right)^n |x_0-\alpha|\xrightarrow[n\to\infty]{}0 \] Donc : \[ |x_n-\alpha|\to 0 \quad\Rightarrow\quad \lim_{n\to\infty}x_n=\alpha \]\( \displaystyle \lim_{n\to\infty} x_n=\alpha \)

-

EXERCICE 2 :

1)

-

a) Montrer que pour tout entier \(k\in\{1,2,\dots,n-1\}\) et tout réel \(x\in\left[\dfrac{k}{n},\dfrac{k+1}{n}\right]\), on a : \(\ln\!\left(\dfrac{k}{n}\right)\le \ln(x)\le \ln\!\left(\dfrac{k+1}{n}\right)\)Corrigé :La fonction \(\ln(x)\) est strictement croissante sur \(]0,+\infty[\). Si \(x\in\left[\dfrac{k}{n},\dfrac{k+1}{n}\right]\), alors : \[ \frac{k}{n}\le x\le \frac{k+1}{n} \quad\Longrightarrow\quad \ln\!\left(\frac{k}{n}\right)\le \ln(x)\le \ln\!\left(\frac{k+1}{n}\right). \]

-

b) En déduire que : \[ \forall k\in\{1,2,\dots,n-1\},\quad \frac{1}{n}\ln\!\left(\frac{k}{n}\right)\le \int_{\frac{k}{n}}^{\frac{k+1}{n}}\ln(x)\,dx \le \frac{1}{n}\ln\!\left(\frac{k+1}{n}\right) \]Corrigé :D’après (a), pour tout \(x\in\left[\dfrac{k}{n},\dfrac{k+1}{n}\right]\) : \[ \ln\!\left(\frac{k}{n}\right)\le \ln(x)\le \ln\!\left(\frac{k+1}{n}\right). \] En intégrant sur \(\left[\dfrac{k}{n},\dfrac{k+1}{n}\right]\), on obtient : \[ \int_{\frac{k}{n}}^{\frac{k+1}{n}}\ln\!\left(\frac{k}{n}\right)\,dx \le \int_{\frac{k}{n}}^{\frac{k+1}{n}}\ln(x)\,dx \le \int_{\frac{k}{n}}^{\frac{k+1}{n}}\ln\!\left(\frac{k+1}{n}\right)\,dx. \] Comme \(\ln\!\left(\frac{k}{n}\right)\) et \(\ln\!\left(\frac{k+1}{n}\right)\) sont constantes : \[ \ln\!\left(\frac{k}{n}\right)\!\int_{\frac{k}{n}}^{\frac{k+1}{n}}dx \le \int_{\frac{k}{n}}^{\frac{k+1}{n}}\ln(x)\,dx \le \ln\!\left(\frac{k+1}{n}\right)\!\int_{\frac{k}{n}}^{\frac{k+1}{n}}dx. \] Or : \[ \int_{\frac{k}{n}}^{\frac{k+1}{n}}dx=\frac{1}{n}. \] Donc : \[ \forall k\in\{1,2,\dots,n-1\},\quad \frac{1}{n}\ln\!\left(\frac{k}{n}\right)\le \int_{\frac{k}{n}}^{\frac{k+1}{n}}\ln(x)\,dx \le \frac{1}{n}\ln\!\left(\frac{k+1}{n}\right). \]

2)

-

a) Montrer que : \[ \forall n\ge 2,\quad \sum_{k=1}^{n-1}\frac{1}{n}\ln\!\left(\frac{k}{n}\right) \le \int_{\frac1n}^{1}\ln(x)\,dx \le \sum_{k=2}^{n}\frac{1}{n}\ln\!\left(\frac{k}{n}\right) \]Corrigé :En sommant l’inégalité de 1.b) pour \(k=1\) à \(n-1\), on obtient : \[ \sum_{k=1}^{n-1}\frac{1}{n}\ln\!\left(\frac{k}{n}\right) \le \sum_{k=1}^{n-1}\int_{\frac{k}{n}}^{\frac{k+1}{n}}\ln(x)\,dx = \int_{\frac1n}^{1}\ln(x)\,dx. \] De même : \[ \int_{\frac1n}^{1}\ln(x)\,dx = \sum_{k=1}^{n-1}\int_{\frac{k}{n}}^{\frac{k+1}{n}}\ln(x)\,dx \le \sum_{k=1}^{n-1}\frac{1}{n}\ln\!\left(\frac{k+1}{n}\right) = \sum_{k=2}^{n}\frac{1}{n}\ln\!\left(\frac{k}{n}\right). \]\(\displaystyle \sum_{k=1}^{n-1}\frac{1}{n}\ln\!\left(\frac{k}{n}\right) \le \int_{\frac1n}^{1}\ln(x)\,dx \le \sum_{k=2}^{n}\frac{1}{n}\ln\!\left(\frac{k}{n}\right) \)

-

b) En déduire que : \[ \forall n\ge 2,\quad u_n \le \int_{\frac1n}^{1}\ln(x)\,dx \le u_n - \frac{1}{n}\ln\!\left(\frac{1}{n}\right) \]Corrigé :D’après 2.a) : \[ \sum_{k=1}^{n-1}\frac{1}{n}\ln\!\left(\frac{k}{n}\right) \le \int_{\frac1n}^{1}\ln(x)\,dx \le \sum_{k=2}^{n}\frac{1}{n}\ln\!\left(\frac{k}{n}\right). \] Or, par définition : \[ u_n=\frac{1}{n}\sum_{k=1}^{n-1}\ln\!\left(\frac{k}{n}\right). \] Et : \[ \sum_{k=2}^{n}\frac{1}{n}\ln\!\left(\frac{k}{n}\right) = \frac{1}{n}\sum_{k=1}^{n-1}\ln\!\left(\frac{k}{n}\right) -\frac{1}{n}\ln\!\left(\frac{1}{n}\right) = u_n-\frac{1}{n}\ln\!\left(\frac{1}{n}\right). \] Donc : \[ u_n \le \int_{\frac1n}^{1}\ln(x)\,dx \le u_n-\frac{1}{n}\ln\!\left(\frac{1}{n}\right). \]\(\displaystyle u_n \le \int_{\frac1n}^{1}\ln(x)\,dx \le u_n-\frac{1}{n}\ln\!\left(\frac{1}{n}\right) \)

-

c) Montrer que : \[ \forall n\ge 2,\quad -1+\frac{1}{n}\le u_n \le -1+\frac{1}{n}-\frac{1}{n}\ln\!\left(\frac{1}{n}\right) \]Corrigé :D’après 2.b) : \[ u_n \le \int_{\frac1n}^{1}\ln(x)\,dx \le u_n-\frac{1}{n}\ln\!\left(\frac{1}{n}\right). \] Calculons : \[ \int_{\frac1n}^{1}\ln(x)\,dx =\left[x\ln x-x\right]_{\frac1n}^{1}. \] Donc : \[ \int_{\frac1n}^{1}\ln(x)\,dx =(1\cdot\ln 1-1)-\left(\frac1n\ln\!\left(\frac1n\right)-\frac1n\right) =-1+\frac1n-\frac1n\ln\!\left(\frac1n\right). \] En remplaçant dans l’encadrement : \[ u_n \le -1+\frac1n-\frac1n\ln\!\left(\frac1n\right), \] et \[ -1+\frac1n-\frac1n\ln\!\left(\frac1n\right) \le u_n-\frac1n\ln\!\left(\frac1n\right) \quad\Longrightarrow\quad -1+\frac1n\le u_n. \]\(\displaystyle \forall n\ge 2,\quad -1+\frac{1}{n}\le u_n \le -1+\frac{1}{n}-\frac{1}{n}\ln\!\left(\frac{1}{n}\right) \)

-

d) Déterminer \(\displaystyle\lim_{n\to +\infty}u_n\)Corrigé :D’après 2.c) : \[ -1+\frac{1}{n}\le u_n \le -1+\frac{1}{n}-\frac{1}{n}\ln\!\left(\frac{1}{n}\right). \] Or : \[ -1+\frac1n \xrightarrow[n\to\infty]{} -1, \qquad -\frac{1}{n}\ln\!\left(\frac{1}{n}\right) = \frac{\ln n}{n} \xrightarrow[n\to\infty]{}0. \] Donc : \[ -1+\frac{1}{n}-\frac{1}{n}\ln\!\left(\frac{1}{n}\right)\xrightarrow[n\to\infty]{}-1. \] Par encadrement : \[ \lim_{n\to +\infty}u_n=-1. \]\(\displaystyle \lim_{n\to +\infty}u_n=-1\)

EXERCICE 3 :

Partie I

1)

-

a) Vérifier que : \[ (E_\theta)\iff \left(2z+(1-i)e^{i\theta}\right)^2=\left((1+i)e^{i\theta}\right)^2 \]Corrigé :On a : \[ (E_\theta):\ z^2+(1-i)e^{i\theta}z - i e^{2i\theta}=0 \quad\Longleftrightarrow\quad z^2+(1-i)e^{i\theta}z = i e^{2i\theta}. \]Multiplions par \(4\) : \[ 4z^2+4(1-i)e^{i\theta}z = 4i e^{2i\theta}. \] Écrivons le membre de gauche sous forme de carré : \[ (2z)^2 + 2\cdot(2z)\cdot(1-i)e^{i\theta} = 4i e^{2i\theta}. \]Ajoutons \(\big((1-i)e^{i\theta}\big)^2=(1-i)^2e^{2i\theta}\) aux deux membres : \[ (2z)^2 + 2\cdot(2z)\cdot(1-i)e^{i\theta} + (1-i)^2e^{2i\theta} = 4i e^{2i\theta} + (1-i)^2e^{2i\theta}. \] Donc : \[ \left(2z+(1-i)e^{i\theta}\right)^2 = \left((1-i)^2+4i\right)e^{2i\theta}. \]Or \((1-i)^2=1-2i+i^2=-2i\). Ainsi : \[ \left((1-i)^2+4i\right)e^{2i\theta}=(-2i+4i)e^{2i\theta}=2i\,e^{2i\theta}. \] Et comme \((1+i)^2=1+2i+i^2=2i\), on obtient : \[ 2i\,e^{2i\theta}=(1+i)^2e^{2i\theta}=\left((1+i)e^{i\theta}\right)^2. \]\(\left(2z+(1-i)e^{i\theta}\right)^2=\left((1+i)e^{i\theta}\right)^2\)

-

b) En déduire les deux solutions \(z_1\) et \(z_2\) avec \(\mathrm{Im}(z_1)\le 0\)Corrigé :De (a), on a : \[ 2z+(1-i)e^{i\theta}=\pm(1+i)e^{i\theta}. \] Donc : \[ z=\frac12\left[\pm(1+i)e^{i\theta}-(1-i)e^{i\theta}\right] =\frac{e^{i\theta}}{2}\left[\pm(1+i)-(1-i)\right]. \]\(z_1=-e^{i\theta}\quad(\mathrm{Im}(z_1)\le 0),\qquad z_2=i\,e^{i\theta}\)

-

c) Montrer que : \[ \frac{z_1+1}{z_2+i}=-\tan\!\left(\frac{\theta}{2}\right) \]Corrigé :En utilisant \(z_1=-e^{i\theta}\) et \(z_2=ie^{i\theta}\) : \[ \frac{z_1+1}{z_2+i} = \frac{-e^{i\theta}+1}{ie^{i\theta}+i} = \frac{1-e^{i\theta}}{i(1+e^{i\theta})}. \]Écrivons avec les formules d’Euler : \[ \frac{1-e^{i\theta}}{1+e^{i\theta}} = \frac{e^{i\theta/2}\left(e^{-i\theta/2}-e^{i\theta/2}\right)} {e^{i\theta/2}\left(e^{-i\theta/2}+e^{i\theta/2}\right)} = \frac{-2i\sin(\theta/2)}{2\cos(\theta/2)} = -i\tan\!\left(\frac{\theta}{2}\right). \] Donc : \[ \frac{1-e^{i\theta}}{i(1+e^{i\theta})} = \frac{-i\tan(\theta/2)}{i} = -\tan\!\left(\frac{\theta}{2}\right). \]\(\displaystyle \frac{z_1+1}{z_2+i}=-\tan\!\left(\frac{\theta}{2}\right)\)

-

d) En déduire la forme exponentielle de \(\dfrac{z_1+i z_2}{z_2+i}\)Corrigé :\[ \frac{z_1+i z_2}{z_2+i} = \frac{-e^{i\theta}+i\cdot i e^{i\theta}}{ie^{i\theta}+i} = \frac{-e^{i\theta}-e^{i\theta}}{i(1+e^{i\theta})} = \frac{-2e^{i\theta}}{i(1+e^{i\theta})}. \]Or : \[ 1+e^{i\theta} = e^{i\theta/2}\left(e^{-i\theta/2}+e^{i\theta/2}\right) = 2\cos\!\left(\frac{\theta}{2}\right)e^{i\theta/2}. \] Donc : \[ \frac{-2e^{i\theta}}{i\cdot 2\cos(\theta/2)e^{i\theta/2}} = \frac{-e^{i\theta/2}}{i\cos(\theta/2)}. \]Comme \(\dfrac{1}{i}=e^{-i\pi/2}\), on obtient : \[ \frac{-e^{i\theta/2}}{i\cos(\theta/2)} = -\frac{1}{\cos(\theta/2)}\,e^{i\theta/2}\,e^{-i\pi/2} = -\frac{1}{\cos(\theta/2)}\exp\!\left(i\left(\frac{\theta}{2}-\frac{\pi}{2}\right)\right). \]\(\displaystyle \frac{z_1+i z_2}{z_2+i} = -\frac{1}{\cos(\theta/2)}\exp\!\left(i\left(\frac{\theta}{2}-\frac{\pi}{2}\right)\right) \)

Partie II

1)

-

a) Déterminer l’affixe \(p\) de \(P\) image de \(Q\) par la rotation \(R\)Corrigé :La rotation \(R\) d’angle \(\dfrac{\pi}{2}\) autour de \(O\) correspond à la multiplication par \(e^{i\pi/2}=i\). Ainsi : \[ p=q\cdot i = me^{i\theta}\cdot i = i m e^{i\theta}. \]

-

b) Vérifier que \(R(A)=C\)Corrigé :Comme \(a=e^{i\theta}\), on a : \[ R(a)=ia=ie^{i\theta}. \] Or : \[ c=b-a=(1+i)e^{i\theta}-e^{i\theta}=ie^{i\theta}. \] Donc \(R(A)=C\).\(R(A)=C\)

2)

-

a) Montrer que : \(\ \dfrac{p-a}{h}=\dfrac{m^2+1}{m}i\ \) et \(\ \dfrac{h-a}{p-a}=\dfrac{1}{m^2+1}\)Corrigé :On a : \[ a=e^{i\theta},\qquad p=ime^{i\theta},\qquad h=\frac{m}{m-i}e^{i\theta}. \] Alors : \[ p-a=e^{i\theta}(im-1). \] Donc : \[ \frac{p-a}{h} = \frac{e^{i\theta}(im-1)}{\frac{m}{m-i}e^{i\theta}} = \frac{im-1}{\frac{m}{m-i}} = \left(\frac{im-1}{m}\right)(m-i). \]Calculons le numérateur : \[ (im-1)(m-i)=im^2-i^2m-m+i=i(m^2+1). \] Ainsi : \[ \frac{p-a}{h}=\frac{i(m^2+1)}{m} \quad\Rightarrow\quad \boxed{\frac{p-a}{h}=\frac{m^2+1}{m}\,i}. \]Ensuite : \[ \frac{h-a}{p-a} = \frac{\frac{m}{m-i}e^{i\theta}-e^{i\theta}}{e^{i\theta}(im-1)} = \frac{\frac{m-(m-i)}{m-i}}{im-1} = \frac{\frac{i}{m-i}}{im-1} = \frac{i}{(m-i)(im-1)}. \] Or : \[ (m-i)(im-1)=im^2-m-i^2m+i=i(m^2+1). \] Donc : \[ \boxed{\frac{h-a}{p-a}=\frac{i}{i(m^2+1)}=\frac{1}{m^2+1}}. \]

-

b) En déduire que \(H\) est le projeté orthogonal du point \(O\) sur la droite \((AP)\)Corrigé :On a montré que : \[ \frac{h-a}{p-a}\in\mathbb{R} \quad\Rightarrow\quad \overrightarrow{AH}\ \text{et}\ \overrightarrow{AP}\ \text{sont colinéaires} \ \Rightarrow\ H\in(AP). \] Et : \[ \frac{p-a}{h}\in i\mathbb{R} \quad\Rightarrow\quad \overrightarrow{OH}\perp \overrightarrow{AP}. \] Donc \(H\) est le projeté orthogonal de \(O\) sur \((AP)\).\(H\) est le projeté orthogonal de \(O\) sur \((AP)\)

-

c) Montrer que : \(\displaystyle \frac{b-h}{q-h}=\frac{1}{m}i\)Corrigé :\[ \frac{b-h}{q-h} = \frac{(1+i)e^{i\theta}-\dfrac{m}{m-i}e^{i\theta}}{me^{i\theta}-\dfrac{m}{m-i}e^{i\theta}} \] \[ = \frac{(1+i)-\dfrac{m}{m-i}}{m-\dfrac{m}{m-i}} \] \[ = \frac{\dfrac{(1+i)(m-i)-m}{m-i}}{\dfrac{m(m-i)-m}{m-i}} \] \[ = \frac{(1+i)(m-i)-m}{m(m-i)-m} \] \[ = \frac{(m+1)+i(m-1)-m}{m^2-im-m} = \frac{1+i(m-1)}{m(m-1-i)} \] \[ = \frac{1+i(m-1)}{m(m-1-i)}\cdot\frac{m-1+i}{m-1+i} \] \[ = \frac{[1+i(m-1)](m-1+i)}{m\big((m-1)^2+1\big)} \] \[ = \frac{i\big((m-1)^2+1\big)}{m\big((m-1)^2+1\big)} = \frac{i}{m} \] \[ = \frac{1}{m}\,i \]\(\displaystyle \frac{b-h}{q-h}=\frac{1}{m}i\)

-

d) En déduire que les droites \((QH)\) et \((HB)\) sont perpendiculairesCorrigé :On a montré : \[ \frac{b-h}{q-h}=\frac{1}{m}i\in i\mathbb{R}. \] Donc les vecteurs \(\overrightarrow{HQ}\) et \(\overrightarrow{HB}\) sont orthogonaux, d’où : \[ (QH)\perp(HB). \]\((QH)\perp(HB)\)

-

e) Montrer que les points \(A,Q,H,B\) sont cocycliquesCorrigé :On utilise la propriété : \[ A,Q,H,B\ \text{sont cocycliques} \iff \frac{b-q}{b-a}\cdot\frac{h-a}{h-q}\in\mathbb{R}. \] On a : \[ \frac{b-q}{b-a}=\frac{1+i-m}{i}, \qquad \frac{h-a}{h-q}=\frac{i}{m(1-m+i)}. \] Donc : \[ \frac{b-q}{b-a}\cdot\frac{h-a}{h-q} = \frac{1+i-m}{m(1-m+i)}. \]Posons \(z=1-m+i\). Alors \(1+i-m=z\) et \(\overline{z}=1-m-i\). Ainsi : \[ \frac{1+i-m}{m(1-m+i)}=\frac{z}{mz}=\frac{1}{m}\in\mathbb{R}. \] Donc \(A,Q,H,B\) sont cocycliques.\(A,Q,H,B\) sont cocycliques

EXERCICE 4 :

1) On suppose que \((E)\) admet une solution \((x_0,y_0)\)

-

a) Montrer que : \(d \text{ divise } bc\)Corrigé :Comme \((x_0,y_0)\in\mathbb{Z}\times\mathbb{Z}\) est solution, on a : \[ y_0=\frac{a}{b}x_0-\frac{c}{d}. \] \[ \frac{a}{b}x_0-y_0=\frac{c}{d}. \] \[ \frac{ax_0-by_0}{b}=\frac{c}{d}. \] \[ d(ax_0-by_0)=bc. \] \[ \Rightarrow\ d \text{ divise } bc. \]\(d \text{ divise } bc\)

-

b) En déduire que : \(d \text{ divise } b\)Corrigé :On sait que \(pgcd(c,d)=1\) et que \(d \text{ divise } bc\).

Par le théorème de Gauss : \[ d \text{ divise } b. \]\(d \text{ divise } b\)

2) On suppose que \(d \text{ divise } b\) et on pose \(b=nd\) avec \(n\in\mathbb{N}^*\)

-

a) Montrer qu’il existe \((u,v)\in\mathbb{Z}\times\mathbb{Z}\) tel que : \(dnu-av=1\)Corrigé :Comme \(b=nd\) et \(pgcd(a,b)=1\), on a : \[ pgcd(a,nd)=1. \] Donc \(pgcd(dn,-a)=1\).

D’après le théorème de Bézout, il existe \(u,v\in\mathbb{Z}\) tels que : \[ dnu+(-a)v=1 \quad\Longleftrightarrow\quad dnu-av=1. \]\(\exists (u,v)\in\mathbb{Z}^2:\ dnu-av=1\)

-

b) En déduire que l’ensemble des solutions de \((E)\) est : \(\;S=\{(-vcn+bk\,;\,-ucn+ak)\mid k\in\mathbb{Z}\}\)Corrigé :Cherchons \((x,y)\in\mathbb{Z}\times\mathbb{Z}\) solution de : \[ y=\frac{a}{b}x-\frac{c}{d}. \] \[ \frac{a}{b}x-y=\frac{c}{d} \quad\Longleftrightarrow\quad ax-by=\frac{bc}{d}. \] Or \(b=nd\), donc : \[ ax-nd\,y=nc. \]Comme \(dnu-av=1\), en multipliant par \(cn\), on obtient : \[ dnu\,(cn)-av\,(cn)=cn \quad\Longleftrightarrow\quad a(-vcn)-nd(-ucn)=nc. \] Ainsi, une solution particulière est : \[ x_0=-vcn,\qquad y_0=-ucn. \]L’équation \(ax-nd\,y=nc\) est une équation diophantienne. La solution générale s’écrit alors : \[ x=x_0+bk=-vcn+bk,\qquad y=y_0+ak=-ucn+ak,\qquad k\in\mathbb{Z}. \] Donc : \[ S=\{(-vcn+bk\,;\,-ucn+ak)\mid k\in\mathbb{Z}\}. \]\(S=\{(-vcn+bk\,;\,-ucn+ak)\mid k\in\mathbb{Z}\}\)

3) Résoudre dans \(\mathbb{Z}\times\mathbb{Z}\) l’équation \((F):\; y=\dfrac{3}{2975}x-\dfrac{2}{119}\)

-

Corrigé :On a : \[ 2975=119\times 25 \quad\Rightarrow\quad b=2975,\ d=119,\ a=3,\ c=2,\ n=25. \] On doit résoudre : \[ dnu-av=1 \quad\Longleftrightarrow\quad 119\cdot 25\,u-3v=1 \quad\Longleftrightarrow\quad 2975u-3v=1. \]On peut prendre \((u,v)=(-1,-992)\) car : \[ 2975(-1)-3(-992)= -2975+2976=1. \]Alors une solution particulière est : \[ x_0=-vcn= -(-992)\cdot 2\cdot 25=49600, \qquad y_0=-ucn= -(-1)\cdot 2\cdot 25=50. \]Donc l’ensemble des solutions est : \[ S=\{(x_0+bk\,;\,y_0+ak)\mid k\in\mathbb{Z}\} = \{(49600+2975k\,;\,50+3k)\mid k\in\mathbb{Z}\}. \]\(S=\{(49600+2975k\,;\,50+3k)\mid k\in\mathbb{Z}\}\)

EXERCICE 5 :

On rappelle que \(\big(M_3(\mathbb{R}), +, \times\big)\) est un anneau unitaire non commutatif, de zéro la matrice :

et d’unité la matrice :

On munit l’ensemble \( E=\{x+yi\mid x\in\mathbb{Z}\ \text{et}\ y\in\mathbb{Z}\} \) par la loi de composition interne \( * \) définie par :

Partie I

1)

-

a) Vérifier que : \((1 - i) * (3 + 2i) = -2 + i\)Corrigé :On a : \[ (1 - i) * (3 + 2i) = (1 + (-1)^{-1} \cdot 3) + (-1 + 2)i \] \[ = (1 + (-1) \cdot 3) + (1)i \] \[ = (1 - 3) + i \] \[ = -2 + i \]\((1 - i) * (3 + 2i) = -2 + i\)

-

b) Montrer que la loi \( * \) n'est pas commutative dans \(E\)Corrigé :On a : \[ (1 - i) * (3 + 2i) = -2 + i \] Donc : \[ (3 + 2i) * (1 - i) = (3 + (-1)^2 \cdot 1) + (2 - 1)i \] \[ = (3 + 1) + i \] \[ = 4 + i \] Or, \(-2 + i \neq 4 + i\), donc la loi \( * \) n'est pas commutative.La loi \( * \) n'est pas commutative dans \(E\).

2) Montrer que la loi \( * \) est associative dans \(E\)

-

Corrigé :Soient \(z_1 = x + yi\), \(z_2 = x' + y'i\), \(z_3 = x'' + y''i\).

On calcule : \[ (z_1 * z_2) * z_3 = \left(x + (-1)^y x' + (y + y')i\right) * (x'' + y''i) \] \[ = \left((x + (-1)^y x') + (-1)^{y + y'} x''\right) + (y + y' + y'')i \] \[ = x + (-1)^y x' + (-1)^{y + y'} x'' + (y + y' + y'')i \] De même : \[ z_1 * (z_2 * z_3) = (x + yi) * \left(x' + (-1)^{y'} x'' + (y' + y'')i\right) \] \[ = x + (-1)^y(x' + (-1)^{y'} x'') + (y + y' + y'')i \] \[ = x + (-1)^y x' + (-1)^y (-1)^{y'} x'' + (y + y' + y'')i \] \[ = x + (-1)^y x' + (-1)^{y + y'} x'' + (y + y' + y'')i \] Donc \( * \) est associative.La loi \( * \) est associative dans \(E\).

3) Montrer que \(0\) est l'élément neutre pour \( * \) dans \(E\)

-

Corrigé :Soit \(z = x + yi \in E\). \[ 0 * z = (0 + 0i) * (x + yi) = (0 + (-1)^0 x) + (0 + y)i = x + yi = z \] \[ z * 0 = (x + yi) * (0 + 0i) = (x + (-1)^y \cdot 0) + (y + 0)i = x + yi = z \] Donc \(0\) est élément neutre pour \( * \) dans \(E\).\(0\) est l'élément neutre pour \( * \) dans \(E\).

4) a) Vérifier que \((x + yi) * ((-1)^{y+1}x - yi) = 0\)

-

Corrigé :On pose \(z = x + yi\), \(z' = (-1)^{y+1}x - yi\).

Alors : \[ z * z' = (x + (-1)^y \cdot (-1)^{y+1} x) + (y - y)i \] \[ = x + (-1)^y(-1)^{y+1}x + 0i \] \[ = x + (-1)^{2y+1}x = x(1 + (-1)^{2y+1}) = 0 \] car \( (-1)^{2y+1} = -1\) (puisque \(2y+1\) est impair), donc \(1-1=0\).\((x + yi) * ((-1)^{y+1}x - yi) = 0\)

-

b) Montrer que \((E, *)\) est un groupe non commutatifCorrigé :

- \( * \) est associative (question 2).

- \(0\) est l'élément neutre (question 3).

- Pour tout \(z = x + yi\), on a vu que \(z' = (-1)^{y+1}x - yi\) est un inverse à gauche, et de même on peut vérifier à droite.

- \( * \) n'est pas commutative (question 1-b).

\((E,*)\) est un groupe non commutatif.

Partie II

Soient les deux ensembles :

et :

1)

-

a) Montrer que \(F = \{x + 2yi \mid x, y \in \mathbb{Z}\}\) est un sous-groupe de \((E, *)\)Corrigé :i) Soient \(z_1 = x + 2yi\), \(z_2 = x' + 2y'i\) deux éléments de \(F\). \[ z_1 * z_2 = (x + (-1)^{2y}x') + (2y + 2y')i = (x + x') + 2(y + y')i \in F \] ii) \(0 = 0 + 0i \in F\).

iii) Si \(z = x + 2yi\), son inverse est \[ (-1)^{2y+1}x - 2yi = -x - 2yi \in F \] Donc \(F\) est un sous-groupe de \((E, *)\).\(F\) est un sous-groupe de \((E, *)\).

-

b) Montrer que la loi \( * \) est commutative dans \(F\)Corrigé :Si \(y\) et \(y'\) sont pairs, alors \( (-1)^y = (-1)^{y'} = 1\). Donc : \[ (x + 2yi) * (x' + 2y'i) = (x + x') + 2(y + y')i \] \[ = (x' + x) + 2(y' + y)i = (x' + 2y'i) * (x + 2yi) \] Donc \( * \) est commutative dans \(F\).La loi \( * \) est commutative dans \(F\).

2) Soit \(\varphi\) l'application définie de \(F\) vers \(M_3(\mathbb{R})\) par \(\varphi(x + 2yi) = M(x, y)\)

-

-

a) Montrer que \(\varphi\) est un homomorphisme de \((F, *)\) vers \((M_3(\mathbb{R}), \times)\)Corrigé :Soit \(z_1 = x + 2yi\), \(z_2 = x' + 2y'i\). \[ z_1 * z_2 = (x + (-1)^{2y}x') + 2(y + y')i = (x + x') + 2(y + y')i \] \[ \varphi(z_1 * z_2) = M(x + x', y + y') \] Et : \[ M(x, y)= \begin{pmatrix} 1 & x & y \\ 0 & 1 & 0 \\ 0 & 0 & 1 \end{pmatrix} \] \[ M(x, y)\, M(x', y')= \begin{pmatrix} 1 & x + x' & y + y' \\ 0 & 1 & 0 \\ 0 & 0 & 1 \end{pmatrix} = M(x + x', y + y') \] Donc \(\varphi(z_1 * z_2) = \varphi(z_1)\cdot \varphi(z_2)\), ainsi \(\varphi\) est un homomorphisme.\(\varphi\) est un homomorphisme de \((F, *)\) vers \((M_3(\mathbb{R}), \times)\).

-

b) Montrer que \(\varphi(F)=G\)Corrigé :\(\subseteq\) : Si \(z = x + 2yi \in F\), alors \(\varphi(z) = M(x, y) \in G\).

\(\supseteq\) : Tout élément de \(G\) est de la forme \(M(x, y) = \varphi(x + 2yi)\) avec \(x + 2yi \in F\).

Donc \(\varphi(F) = G\).\(\varphi(F)=G\)

-

c) En déduire que \((G, \times)\) est un groupe commutatifCorrigé :\((F, *)\) est un groupe commutatif (question 1-b).

\(\varphi\) est un homomorphisme et \(\varphi(F)=G\).

Donc \((G, \times)\) est un groupe commutatif.\((G,\times)\) est un groupe commutatif.

-